Trees of Significance: Growing community in the shade

TTF team members at Wright Park

Washington's State Tree, the western hemlock, is a charming example of the Pacific Northwest’s ecological majesty. These trees grow in the shade of other trees, and as such, remind us of the importance of the forest’s understory. Because of the way they can thrive in the shaded spaces so many others cannot, hemlocks help increase the density and environmental benefits of our region’s forests, making them some of the most productive ecosystems in the world.

Julia on a hike at East Glacier in Montana. Photo credit: Joe Wolf

Julia Gonzalez-Wolf, TTF’s Communication Coordinator, has a lot in common with the western hemlock: where the tree supports the forests it inhabits standing tall under other trees, Julia supports TTF from behind the camera and editing room as she tells the story of our work.

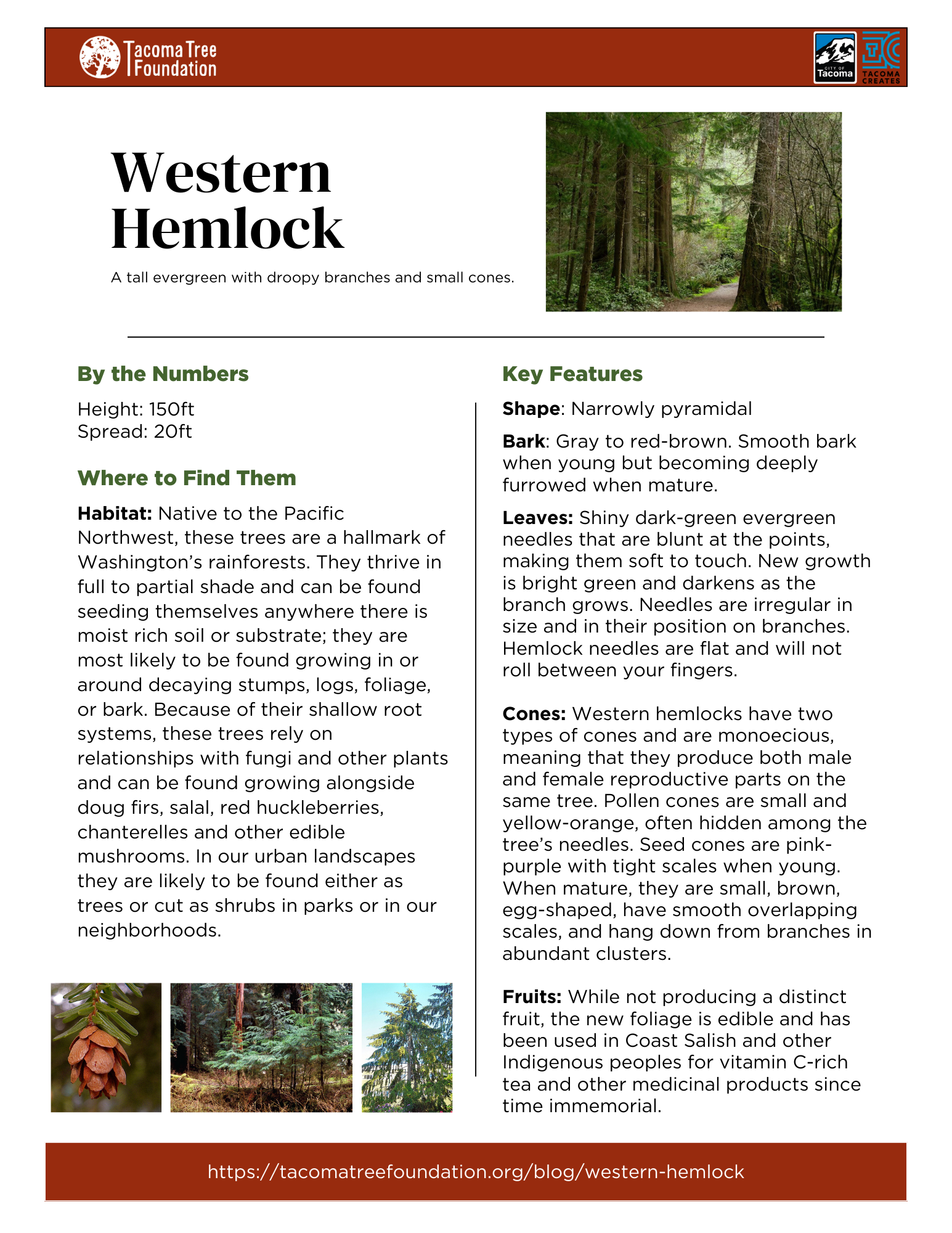

If you’ve ever hiked through Point Defiance Park, or one of western Washington’s other old growth forests where nurse logs are common, you’ve likely come across the western hemlock. In fact, Point Defiance is where Julia first learned to identify the western hemlock while on a walk led by Dr. Romey Haberle in partnership with TTF called “The Green Life around Trees.” Dr. Haberle’s description of the conifer’s needles as lacey and irregular in size and placement stuck with Julia: “I like the way that there is beauty in the unorganized.”

Western Hemlock Credit: Wikimedia

“After each of Romey's presentations, I try to walk away being able to identify a new plant,” Julia said. Learning to identify the western hemlock took a bit of time for her, as the tree is easy to mistake for a deodar cedar or Douglas fir.

With a deodar cedar “[t]he cones are huge, and they sit on the top, and they look like wasps nests to me,” Julia shared. With western hemlocks, the seed cones hang down from the tree’s branches and are small, have large scales, are pinkish-purple when young, and are often produced in abundance. Confusion with the Douglas fir can happen when looking at a western hemlock from afar, with the bark of each tree being both gray to red-brown and deeply furrowed when mature, and the overall silhouette and color of each tree resembling the other to some degree.

Minion hemlock and Dougfir Credit: Washington State Department of Natural Resources

These similarities are further complicated by the fact that western hemlocks love to seed themselves in the woody substrate that gathers at the base of Douglas firs thanks to their bark and needles. They become what are referred to as “minions”, growing under and eventually becoming tangled within the Doug-fir’s foliage. Up close one can see that the hemlock’s boughs will drape downward off the main branches while the Douglas fir’s will be stiffer. Additionally, the size of the cones and texture of the needles will be telling, as Doug-fir cones have the distinctive “mouse tail” under the scales of their cones. They are larger than the hemlock’s. And, while the hemlock needles are flat and will not roll between your fingers, the Doug-fir’s will.

Julia’s photography skills, attention to detail, and excitement to learn have helped her develop the trained eye needed to identify the western hemlock correctly.

Julia’s purple flower.

Her love of photography began with the photos she would take on her mom’s old flip phone. “I was just taking photos of everything and trying to make things look cool. I specifically remember thinking, ‘How can I angle this? How can I get a new perspective on this? How can I look at this in a way that is captivating or intriguing?'” Her goal to capture solitary objects and details resulted in a photo of a flower that caught her attention years later: “As I was going through old photos, I thought, ‘This one is pretty good, maybe I should get a camera.’ And, that's how I ended up getting my first camera.”

By high school, she had decided that photography was what she wanted to pursue professionally. She liked that she could go into any field and do photography work. Every space that needs advertising or social media would need photos. “Anything that I enjoy, I can take pictures of. And now I get to take pictures of people planting trees,” Julia said.

Like the trees she photographs, Julia thrives on the dynamic environment we have at TTF. “I like the idea of needing the nutrients from others. We're all putting things back into the soil. And we're all lifting each other up with the energy that we provide.”

Nurse log and hemlock seedlings Credit: Washington State Department of Natural Resources

This is not unlike the relationship that western hemlocks have with nurse logs, fungi, and other plants such as salal and red huckleberries. Hemlocks do not have taproots like most other trees, which would anchor in the soil and provide access to water and nutrient resources found further underground. Instead, they rely on a shallow root system and connections with other species to thrive.

Nurse logs are trees that have fallen and begun to decay, leaving a moist, nutrient rich, and readily available organic substrate for baby trees and plants to root themselves. Hemlocks will even grow directly on older living trees, sometimes many feet above the ground where decaying needles and bark collect. It is within these abundant ecosystems that hemlocks make critical symbiotic relationships with fungi, called ectomycorrhizal relationships, through which they exchange nutrients, water, and even antibodies, and maintain relationships to other plants like salal and red huckleberries.

Being one of our newest full-time staff members at TTF, Julia appreciates the knowledge and expertise passed down to her from more experienced staff and partners: If Julia is a hemlock seedling, her co-workers are a nurse-log ecosystem. “I love learning, and at TTF I get to be a student every day” Julia said. “Working with experts and being able to go to talks for work is so exciting. Getting to soak all [the information] in is really cool.” Julia is a recent graduate from Pacific Lutheran University in Parkland and expressed her gratitude at having found a full-time job that is centered around learning and research. “I honestly didn't expect that I was going to have strong co-worker relationships. Now those relationships are great, and it's not about a grade. I just get to learn for the enjoyment of knowing how cool trees are, and everyone's a nerd, too.”

As the western hemlock grows and the original nurse log continues to decay and turn into soil, the hemlock’s roots follow pathways of readily available nutrients and water, eventually leading down to the ground around the nurse log. Their roots may become exposed, with mature trees seeming to be on stilts as time goes on, but the tree becomes stronger and more resilient as they age.

Having been a part of the TTF community for two years now, Julia is well known and connected in our community. This, in turn, helps her support the rest of us. “Once a photographer is in a certain space long enough, they add to the energy [of a space] and boost it in a way where they're getting candid photos because they're creating that environment” Julia shared. If you’ve ever had your photo taken by Julia you know that her charisma is contagious, helping you to open up more authentically to the camera. Julia’s role as Communications Coordinator is multi-faceted: she develops and manages our social media platforms and website, coordinates our education events, including the Climate Leadership Cohort, co-creates our fundraising campaigns, keeps the channels of communication open with our partners via emails and one-on-ones, as well as photographing all of our events!

In the same way that the hemlock renders empty spaces in forests into supportive and nourishing ecosystems that would otherwise be inhospitable, Julia keeps us connected while capturing the moments that might otherwise go unnoticed by the rest of our staff. In capturing the impact of our work, she turns small moments–a passing smile, a group walking through a neighborhood, the buds of a new tree–into opportunities for genuine connection with everyone we work with.