Parkland: From Wilderness to Unfair Forest

Written by Adela Ramos and Eden Standley

Mahon Prairie in present-day Parkland. Photo: William W. Smith. Source: Richard Osness From Wilderness to Suburb (1976).

How does a thriving wilderness become a suburb with a gravely diminished ecosystem in just a century? For the unincorporated suburb of Parkland, on the outskirts of Tacoma, the answer involves delving into a threefold history of colonization, industrialization, uneven development and disinvestment.

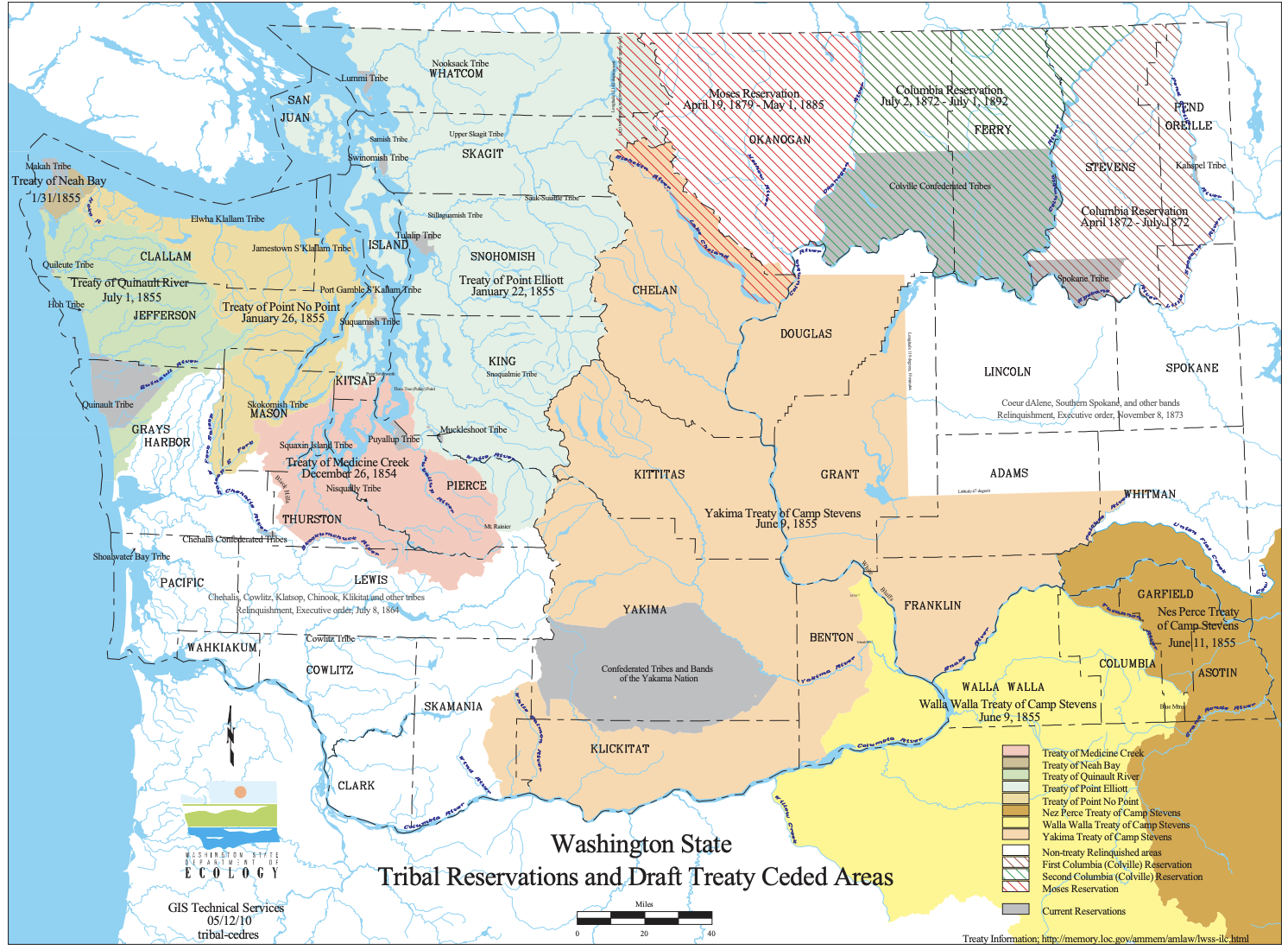

Parkland borders the City of Tacoma’s southern limits at 96th street. Its name alludes to the thriving environment it once was. Development of what is now Parkland began in the late nineteenth century as a result of the 1850 Oregon Land Law (a.k.a Donation Land Act), which opened up designated public lands for homesteading, and the 1854-55 Medicine Creek Treaty.

Source: WA GOIA Map of Tribal and Ceded Lands

To the Nisqually, Puyallup, and Steilacoom Tribes, this land was—and still is—a culturally important area of prairie and coniferous forest. And so it was for the immigrant settlers who derived the name from how its prairie, trees, and streams made it “pretty as a park” (Osness).

Standing at the corner of Pacific Avenue and Garfield Street South, historically one of Parkland’s main throughways, it takes effort to imagine such a place in the midst of today’s strip malls, compacted gravel, sidewalks with scant trees, and the roar of passing cars. Yet čaʔadᶻac (Garry Oaks) and čəbidac (Douglas Firs) stood tall over the prairie and the once overflowing Chambers-Clover Creek watershed, where the Coast Salish, and much later, immigrants, fished for trout and King Salmon. For the settlers, Parkland’s waters also provided irrigation to develop farmland, and Parkland’s old growth trees were felled to fuel the Tacoma logging boom. Thanks to ‘Old Betsy,’ a steam railway that ran down C Street, residents were connected to the port city by way of South Tacoma, and eventually the Parkland-Tacoma streetcar route was developed.

Clearing land east of present day Pacific Avenue, between 112th St. and 128th St. Photo: Ned R. Anderson. Source: Richard Osness From Wilderness to Suburbia.

After navigating the economic downturns and wars of the twentieth century, post-WWII Parkland moved rapidly but unevenly from rural area to suburb. Throughout this time, Pacific Lutheran University (PLU) and Joint Base Lewis McChord (JBLM) became established in the area, and both continue to play an important economic role in the greater Tacoma area. In fact, JBLM employs more area residents than the top 20 employers in Tacoma and Pierce County. An emblem of Parkland’s economic and social prosperity can be found in Parkland Light & Water Company, the oldest mutual utility company in the United States. Yet, as economic boom led to expansion, PLU and JBLM pushed significant portions of the watershed underground to allow for further development. Wilderness and farmland gave way to suburban sprawl, where employees and new residents were not as connected to local farms and businesses (Osness). While this is the same story that has shaped myriad cities and towns across the USA over the past century, Parkland’s challenges are compounded by its status as an unincorporated census-designated place (CDP). This situates it not only on the City of Tacoma’s geographic periphery, but also on the periphery of infrastructure services, such as sidewalks and greening.

Green Blocks: Parkland. What we learned.

For the Tacoma Tree Foundation (TTF), Parkland’s limited access to greening infrastructure must be considered in relation to both the area’s considerably low overall rating on Pierce County’s Equity Index map, which assesses the conditions relating to accessibility, livability, education, economy, climate, and environment. According to data collected by American Forests for the Tree Equity Score project, an average 46% of the population in Parkland identify as people of color, while 31% of the total population are people in poverty, and 36% are children (0-17) or seniors (65+). All of these factors make the people in Parkland more vulnerable to the effects of climate change, especially to urban heat islands. For instance, according to a risk-mapping tool, produced by climate researchers at UW during the heat dome event of 2021, Parkland and Spanaway had the highest average heat related health risks of any other areas in the state, 10% higher than in the City of Tacoma.

Parkland is an example of what Executive Director Lowell Wyse calls the “unfair forest,” an urban forest where only the wealthier, usually whiter neighborhoods, enjoy the health infrastructure that trees provide, while lower income and more diverse neighborhoods are left to face the potentially deadly effects of low tree canopy coverage. For these reasons, the Tacoma Tree Foundation developed its second Green Blocks program in Parkland in February 2023, partnering with Pierce County with funding from the Washington Department of Natural Resources.

Green Blocks is our neighborhood-based greening program designed to grow an equitable tree canopy in the Tacoma urban area. The program’s focus is informed by our mission to strengthen community ties through greening.

Image: Green Blocks: Parkland 2023 project area.

Green Blocks: Parkland began with the goal of distributing 200 trees to residents within our focus area, which stretched from 96th St to 152nd St, from Perimeter Rd to Waller Rd, up Brookdale Rd E and Golden Given Rd E (see map below). Community outreach was essential to the success of the program, especially our commitment to canvassing, which gives us a chance to speak directly with neighbors, make connections, share information, and hear community perspectives on greening.

Eden Standley, a TTF Outreach Specialist and PLU student who lives on campus, hadn’t explored the area until they began canvassing for the program last January. They grew up in Tacoma, where Parkland was often perceived as a high-crime neighborhood, creating a stigma that deemed Parkland unsafe. We spoke with Dr. Laura McCloud, who is the current department chair of sociology and criminal justice at PLU, to learn more about why many Tacomans hold this perception about Parkland. She said that what influences a place to be perceived as “criminal” correlates more strongly with rates of poverty and racial diversity than actual crime rates. Although this perception can lead to disinvestment in an area and eventually worsen conditions and crime rates, this correlation still suggests that Parkland may not be as unsafe as many Tacomans are inclined to believe. For Eden, it was getting to know the people of Parkland through canvassing for Green Blocks: Parkland that transformed their perception.

Over the course of 6 weeks in early 2023, they walked about 45 miles alongside other volunteers, dashing from house to house, hanging door hangers before dusk. Frequently, the canvassers would meet someone who was out in their yard, arriving home from work, or who would meet them at the door after spotting them through the window. The canvassers would greet them with, “Hello! Free trees?”. Eden recalls their excitement at the overwhelming number of people who greeted them with kindness and were interested to hear about the Green Blocks: Parkland project happening in the neighborhood. Everyone had their own tree stories: one resident remembered when Parkland was still “pretty as a park.” She had witnessed the original forest on her street being felled as the land around her was bought and developed. She expressed appreciation for TTF’s efforts to grow the canopy.

Parklanders are passionate about their space and about greening. Through the Green Blocks: Parkland program, TTF and Pierce County distributed roughly 900 trees in total to 255 residents—more than quadruple our initial goal (see map below). 364 of the total trees (40%) were given to 103 residents who lived within the project footprint, 69.7% of those residents had pre-registered, potentially demonstrating the effectiveness of our canvassing and flyering efforts.

To make the maps presented here, we used data collected by Pierce County during the Green Blocks: Parkland tree giveaway. Note that these maps, and all conclusions that can be drawn from them are estimates of the project outcomes based on available, decipherable data, and that the exact numbers given may be marginally higher or lower, but these maps do represent the success of our program on a broad scale.

About the Maps

To qualify to preregister, recipients had to live within the project footprint; those who did not were able to get trees from the giveaway site at the day-of event, but did not qualify for delivery or planting assistance.

There were a few recipients who did not leave complete addresses, and in those cases, their geographic locations were plotted as accurately as possible based on the info they gave.

A Greener Future for Parkland-Spanaway

In Parkland’s diminished prairie and watershed, we have found hope. As we learned through distributing trees at our Green Blocks: Parkland event, current Parkland residents love where they live and are ready to put the park back in Parkland. This prairie land is one of the few places in Washington where the traditional Camas Lily and Garry Oak acorns—essential to the Coast Salish diet and traditions—can be harvested. This is possible in part thanks to renewed understanding of Tribal knowledge and foodways, and work currently underway to repair relationships between PLU, which owns a considerable segment of the prairie, and Coast Salish Tribes. JBLM recently redirected a section of the Clover Creek into a cleaner, fish-friendly channel that will allow the passage of salmon and trout again.

As we reviewed the data from the 2023 program, we noticed that many of the trees given away outside of the project boundary went to residents of the Spanaway area. This points to the real need for community greening in Spanaway, which is why we decided that our next Green Blocks project, coming in the winter of 2024, would be extended to include Spanaway. We will once again be partnering with Pierce County and the Department of Natural Resources, and are excited to announce that our new goal is to distribute 1000 trees to residents in the area! These young trees will help grow a greener and healthier future for Parkland and Spanaway.

Many thanks to Dr. Romey Haberle (PLU, Biology) and Dr. Laura McCloud (PLU, Sociology and Criminal Justice) for supporting our research for this piece.